Dark Mode - Essential not a Preference

by Katie McDermott , CEO, See Me Please

Dark mode is often treated as a nice-to-have rather than a necessity or assistive technology.

Nothing Beats Direct Customer Feedback

Dark mode has emerged as one of the most significant accessibility considerations in digital design, yet it is still often treated as a nice-to-have rather than a fundamental feature. Many organisations adhere to the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) to ensure accessibility compliance, but compliance does not always equate to usability.

For blind and low-vision users, as well as some neurodivergent individuals, dark mode is not just a preference—it is a necessity. It reduces glare, enhances contrast, and extends the time users can comfortably engage with digital content. Without it, users experience fatigue, headaches, and even an inability to complete tasks, ultimately leading to frustration, abandonment, and exclusion from digital services.

When we speak directly to users with lived experience, the importance of dark mode becomes even clearer.

Daniel describes why his phone is permanently set to dark mode:

“My phone's permanently set on a dark mode to reduce the glare of any of the white screens or anything just blasting me in the eyes. It helps me use screens for longer so my eyes don't get as fatigued at the end of the day. Even people who have lost 99% of their vision still have a light sensitivity.”

This statement challenges a common misconception about blindness—many blind individuals still have some residual vision, and light sensitivity remains a significant issue. For them, bright screens are not just inconvenient; they are painful and actively reduce their ability to engage in digital work and communication.

Dan emphasises the connection between screen brightness and headaches and fatigue: “When you have this bright light just blasting you in the eyes, it's painful, it gives you headaches. Most of your job you're doing these days, you're looking at a computer screen. There are very few jobs where you're not looking at a computer screen. So if you want to extend how long you're able to do that work for, you need to try and get the most favourable conditions for your eyes.”

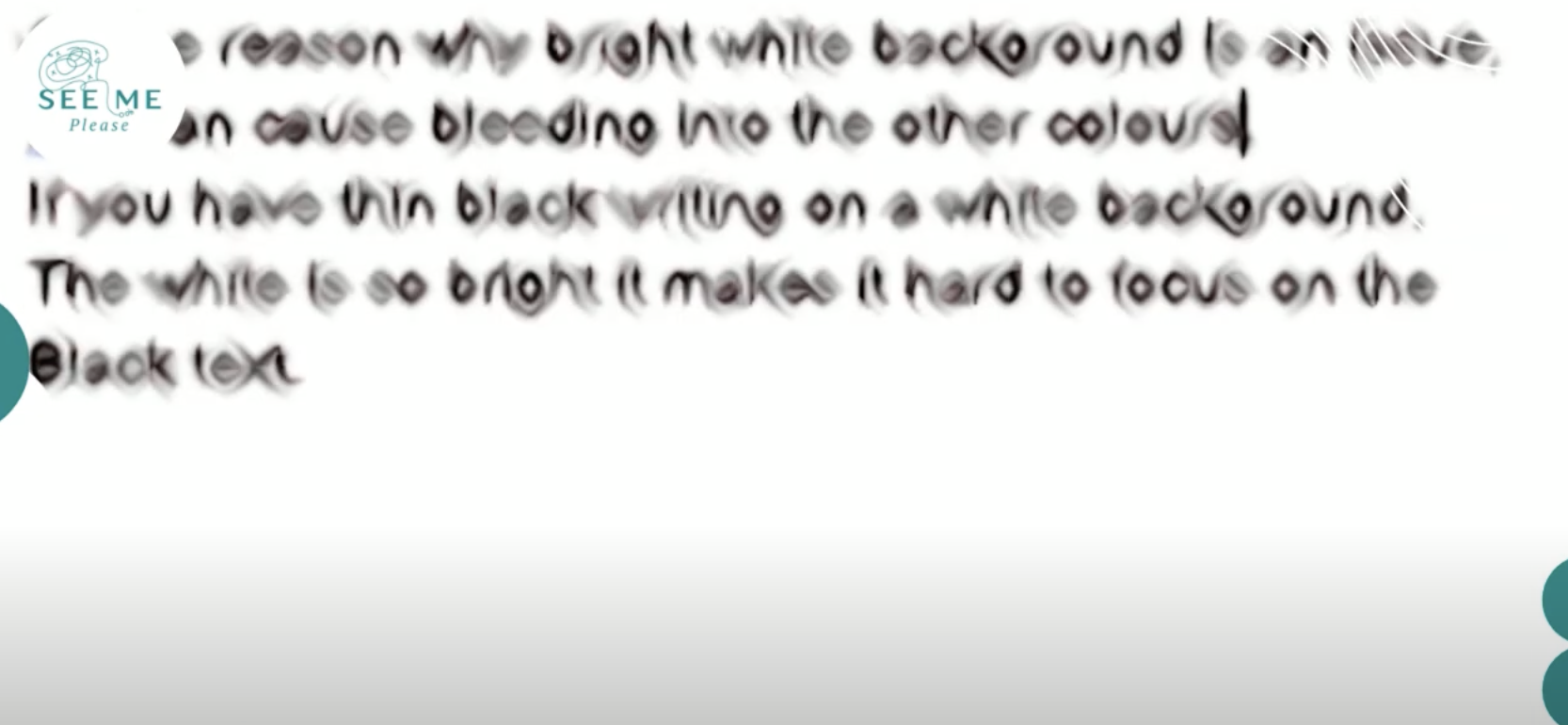

This highlights the occupational accessibility barriers that bright screens create. Digital tools should empower people to work efficiently, not force them into discomfort and early fatigue. Another challenge with bright white backgrounds is the way it affects readability: “A bright white background is an issue because it causes bleeding into the other colours. So if you have thin black writing on a white background, the white's so bright that it kind of makes it hard to look at the black writing.”

The Halation Phenomenon

This phenomenon, known as halation, makes text appear blurred or distorted for many users, reducing legibility and comprehension. Conversely, dark backgrounds with white text provide greater clarity. Patrick, who has a degenerative eye condition explains: “White text on a black background doesn't just look cool, it's much easier on the eyes. When I used white on black, it was easier because the print would stand out much more. Even looking at the time was much easier. The numbers would just jump at you.”

For users with low vision, neurodivergent conditions like dyslexia, and even those experiencing age-related vision decline, dark mode significantly improves readability and usability.

The Most Frequently and Common Requested Feature in User Testing

Despite dark mode's widespread popularity, there is surprisingly little formal research or quantitative data on its accessibility benefits. However, after aggregating insights across multiple See Me Please user testing projects—each involving 18 diverse participants, including 3 blind, 3 with low vision, 3 neurodivergent, 3 Deaf or Hard of Hearing, 3 over 70, and 3 with limited English proficiency—we were struck by how often dark mode emerged as the most requested feature. It was consistently the top accessibility request across companies, often ranking higher than other common accessibility improvements. Based on our experience, we estimate that around 75% of our low vision testers and at least half of our blind testers express a strong preference or need for dark mode.

This aligns with broader user preferences, as many others—including neurodivergent users and those sensitive to screen brightness—also value dark mode for comfort and usability. While accessibility standards often overlook dark mode, our findings suggest it is a critical feature that enhances real-world usability for a wide range of users.

Design and development teams only have so much capacity, and when considering investments in accessibility, it's crucial to prioritise features that deliver the greatest impact for users. Our user testing strongly suggests that dark mode is not just a preference but a necessity, resonating far more than the collective value placed on embedded read-aloud features, which are often included on websites but rarely requested by people with a disability with the same urgency. If organisations are weighing accessibility investments, particularly in enterprise settings, thinking about how dark mode can be integrated—at least in new applications—could provide far greater usability benefits than other commonly implemented accessibility features

WCAG is a Guideline, Not a Guarantee of Usability

WCAG provides an essential foundation for digital accessibility, yet it does not specifically require dark mode support. While it recommends sufficient contrast (WCAG 2.1, Success Criterion 1.4.3), the standard does not ensure that interfaces are comfortable for all users. Studies on dark mode’s impact show that:

- Glare reduction can improve reading efficiency by up to 50% for some low-vision users.

- Contrast sensitivity declines with age, making dark mode particularly beneficial for older adults.

- Neurodivergent users, including those with autism and ADHD, find dark mode less overstimulating, improving focus and usability.

Despite these benefits, many organisations assume meeting WCAG contrast requirements is enough. However, true accessibility is about usability, not just compliance. If a user is technically able to read content but experiences discomfort, pain, or excessive strain, that content is not truly accessible.

The Impact and Workarounds

Why Lack of Dark Mode Causes Abandonment

Without dark mode, users often face severe consequences:

- Headaches and migraines from prolonged exposure to bright screens.

- Blotchy vision caused by high contrast between black text and white backgrounds.

- Shorter screen engagement times, meaning users may be unable to complete essential tasks before discomfort forces them to stop.

- Increased frustration, leading to abandonment of apps, websites, or services.

For businesses and government agencies, failing to offer dark mode creates barriers to service access, particularly for those who rely on assistive technologies.

The Limitations of Forced Dark Mode, Colour Inversion & Plug-ins

Many users rely on plug-ins and third-party tools like Dark Reader, Midnight Lizard, and Stylus to force dark mode on websites that don’t natively support it. While these tools provide short-term solutions, they are essentially overlays, which introduce several accessibility issues.

Overlays modify the display at the browser level, rather than adjusting the UI in a way that is intended, tested, or optimised by the original developers. This can cause:

- Inconsistent colour application – Overlays can misinterpret colours, leading to unexpected contrasts or unreadable text.

- Loss of visual hierarchy – UI elements designed with specific colour emphasis may become indistinguishable, making navigation difficult.

- Accessibility conflicts – Overlays can interfere with built-in accessibility features like screen readers, forcing users to disable them.

- Performance issues – Browser-based dark mode plug-ins increase load times and sometimes cause visual glitches.

One of the biggest misconceptions about overlays is that they solve accessibility problems. In reality, they often introduce new barriers rather than removing them.

The key difference between pushing colour inversion with a plug-in versus native dark mode comes down to control and consistency. Colour inversion, when applied through a plug-in or system-wide setting, works as an overlay that forcibly inverts colours at the browser level rather than adjusting the UI as intended. This can cause significant distortions to images, icons, and visual elements, often making essential content unreadable— for example, a blue sky might turn orange, and important graphs or charts may lose their meaning. Additionally, colour inversion frequently results in inconsistent styling, breaking UI elements, making text difficult to read, and creating poor contrast ratios that worsen accessibility instead of improving it. Users often find themselves constantly adjusting settings, toggling between modes just to complete simple tasks, leading to unnecessary frustration and cognitive load.

In contrast, native dark mode is designed intentionally within an application to provide a seamless and accessible experience. It ensures proper contrast and readability, preserving the original intent of the design while keeping images and key visual cues intact. Native dark mode works smoothly with assistive technologies, including screen readers, and prevents the need for users to rely on third-party fixes. While plug-in-based colour inversion can serve as a temporary workaround, it is ultimately a patchwork solution that introduces new usability issues, whereas native dark mode provides a structured, user-friendly approach that truly enhances accessibility.

The Distortion of Visual Aids and Images in Colour Inversion

Another common workaround is colour inversion, available in operating system accessibility settings. This setting flips light to dark and vice versa, making bright screens easier to tolerate. However, this also inverts images, icons, and visual elements, which can:

- Make images look unnatural or unusable – A blue sky turns orange, and essential visual cues (like coloured warning signs) become misleading.

- Distort graphs, charts, and UI elements – Key visual aids become unreadable, removing important context for data representation.

- Break interface consistency – When websites have some dark UI elements by default, colour inversion can make these unintendedly bright, creating a disjointed and jarring experience.

- Pushing colour inversion on mobile often means default dark settings are reversed, so the user is challenged with a keyboard consuming half their screen now in light colours. Often this results in the user having to toggle between dark and light mode default settings many times just to do something very simple.

This constant toggling between modes adds unnecessary cognitive load and frustration, making simple tasks time-consuming and exhausting.

Instead of relying on overlays and forced inversion, websites and apps should natively support dark mode in their design. A well-implemented dark mode ensures that all visual elements are designed intentionally, avoiding the distortions caused by inversion, colour contrast and legibility are optimised for all users and dark mode can be toggled at the user’s preference, rather than relying on inefficient and frustrating workarounds.

The Global Impact

Globally, over 2.2 billion people have some form of vision impairment, and 1 in 5 people are neurodivergent. Many of these individuals benefit from dark mode, making it a high-impact accessibility feature. Moreover, the value of offering dark mode and benefit so many more users. For example

- Users in low-light environments (e.g., using devices at night)

- People with temporary sensitivity (e.g., after eye surgery)

- Anyone who experiences screen fatigue

The aim should be universal usability, not ticking a box

Dark mode is not just a design trend—it is a fundamental accessibility need. While WCAG provides a great starting point, lived experience must drive digital accessibility efforts. By offering native dark mode support, organisations can create truly inclusive digital experiences and ensure that all users can engage comfortably and effectively.

As Mary, our wise blind tester said “We know what we need and we know what we want from programmes or apps. So it is always best to ask the user.”

Lets start listening on those who rely on accessible online services, rather than obsessing over WCAG conformance.